ABOUT Ollantaytambo

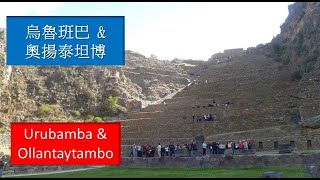

Ollantaytambo, in Quechua Ullantaytampu, which means "granary of God", is a small city in the province of Urubamba, Cusco region.

The city is located about 60 km northwest of Cusco, at an altitude of 2,848 meters above sea level, on the right bank of the Urubamba River. According to legend, the god Viracocha instructed the Incas to build the city.

The 2017 census counted 3,050 inhabitants.

Ollantaytambo is the only remaining example of Inca urbanism. The Inca buildings and terraces as well as the narrow streets of the city are still in their original state.

The main settlement of Ollantaytambo has an orthogonal layout with four longitudinal streets crossed by seven parallel streets. In the center of this grid, the Incas built a large plaza that may have been up to four blocks long; it was open to the east and surrounded by halls and other blocks on its other three sides. All the blocks in the southern half of the city were built to the same design; each consisted of two kanchas, walled enclosures with four one-room buildings around a central courtyard. The buildings in the northern half are more varied in design; however, most are in such poor condition that their original plan is difficult to establish.

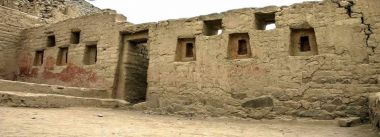

Many of the houses in the town are built with perfectly crafted Inca walls of dark pink stone. The Inca built administrative, agricultural, military, and religious facilities in Ollantaytambo.

On the side of the Ollantaytambo mountain is an imposing Inca complex, popularly known as a fortress for its extraordinarily strong walls. In fact, this complex was strategically located to dominate the Sacred Valley of the Incas. Manco Cápac II also retired here in 1537 after the failed siege of Cuzco to rally his forces against the conquerors.

Architectural historian Jean-Pierre Protzen of the University of California, Berkeley, points out that in the past it has often been argued that the ancient monumental core of Ollantaytambo (for example, the Wall of the Six Monoliths) is the work of the earlier culture. from Tiwanaku and was only reused by the Incas:

An argument remains that the Wall of the Six Monoliths and the defunct structures from which the blocks were recycled predate the Incas and were the work of the earlier Tiahuanaco culture. The argument is supported by the step motif carved into the fourth monolith and the T-shaped mounts carved into various blocks, which are considered hallmarks of Tiahuanaco-style architecture...A variant of this argument is that the elements tiahuanacoides were brought to Ollantaytambo by stonemasons from Lake Titicaca. The only question that arises here is why the stonemasons of Lake Titicaca should remember anything Tiahuanaco when nothing comparable was built for several centuries. If anything reminds me of Tiahuanaco, it's the T-shaped frames and the regularly layered masonry of heavily altered andesite. Many T-shaped lacework can be seen in the Puma Punku complex.

However, according to Protzen, only T-shaped settings are found at Ollantaytambo, while prong settings with a wide range of shapes are found at Tiwanaku.

In 1540, the native population of Ollantaytambo was assigned in charge to Hernando Pizarro.

In the 19th century, the Inca ruins of Ollantaytambo attracted the attention of various foreign explorers; among them, Clements Markham, Ephraim Squier, Charles Wiener, and Ernst Middendorf, who published accounts of their finds.

Hiram Bingham III stopped here in 1911 on his journey up the Urubamba River in search of Machu Picchu.

The valleys of the Urubamba and Patakancha rivers along Ollantaytambo are covered by an extensive set of platforms or agricultural platforms that rise at the bottom of the valleys and ascend the surrounding hills. The platforms allowed agriculture on land that would otherwise be unusable; they also allowed the Incas to take advantage of the different ecological zones created by variations in altitude. The terraces at Ollantaytambo were built to a higher standard than common Inca agricultural terraces; for example, they have higher walls made of cut stones rather than rough field stones. This type of high-prestige terraces is also found in other royal Inca haciendas such as Chinchero, Pisaq and Yucay.

The city is located about 60 km northwest of Cusco, at an altitude of 2,848 meters above sea level, on the right bank of the Urubamba River. According to legend, the god Viracocha instructed the Incas to build the city.

The 2017 census counted 3,050 inhabitants.

Ollantaytambo is the only remaining example of Inca urbanism. The Inca buildings and terraces as well as the narrow streets of the city are still in their original state.

The main settlement of Ollantaytambo has an orthogonal layout with four longitudinal streets crossed by seven parallel streets. In the center of this grid, the Incas built a large plaza that may have been up to four blocks long; it was open to the east and surrounded by halls and other blocks on its other three sides. All the blocks in the southern half of the city were built to the same design; each consisted of two kanchas, walled enclosures with four one-room buildings around a central courtyard. The buildings in the northern half are more varied in design; however, most are in such poor condition that their original plan is difficult to establish.

Many of the houses in the town are built with perfectly crafted Inca walls of dark pink stone. The Inca built administrative, agricultural, military, and religious facilities in Ollantaytambo.

On the side of the Ollantaytambo mountain is an imposing Inca complex, popularly known as a fortress for its extraordinarily strong walls. In fact, this complex was strategically located to dominate the Sacred Valley of the Incas. Manco Cápac II also retired here in 1537 after the failed siege of Cuzco to rally his forces against the conquerors.

Architectural historian Jean-Pierre Protzen of the University of California, Berkeley, points out that in the past it has often been argued that the ancient monumental core of Ollantaytambo (for example, the Wall of the Six Monoliths) is the work of the earlier culture. from Tiwanaku and was only reused by the Incas:

An argument remains that the Wall of the Six Monoliths and the defunct structures from which the blocks were recycled predate the Incas and were the work of the earlier Tiahuanaco culture. The argument is supported by the step motif carved into the fourth monolith and the T-shaped mounts carved into various blocks, which are considered hallmarks of Tiahuanaco-style architecture...A variant of this argument is that the elements tiahuanacoides were brought to Ollantaytambo by stonemasons from Lake Titicaca. The only question that arises here is why the stonemasons of Lake Titicaca should remember anything Tiahuanaco when nothing comparable was built for several centuries. If anything reminds me of Tiahuanaco, it's the T-shaped frames and the regularly layered masonry of heavily altered andesite. Many T-shaped lacework can be seen in the Puma Punku complex.

However, according to Protzen, only T-shaped settings are found at Ollantaytambo, while prong settings with a wide range of shapes are found at Tiwanaku.

In 1540, the native population of Ollantaytambo was assigned in charge to Hernando Pizarro.

In the 19th century, the Inca ruins of Ollantaytambo attracted the attention of various foreign explorers; among them, Clements Markham, Ephraim Squier, Charles Wiener, and Ernst Middendorf, who published accounts of their finds.

Hiram Bingham III stopped here in 1911 on his journey up the Urubamba River in search of Machu Picchu.

The valleys of the Urubamba and Patakancha rivers along Ollantaytambo are covered by an extensive set of platforms or agricultural platforms that rise at the bottom of the valleys and ascend the surrounding hills. The platforms allowed agriculture on land that would otherwise be unusable; they also allowed the Incas to take advantage of the different ecological zones created by variations in altitude. The terraces at Ollantaytambo were built to a higher standard than common Inca agricultural terraces; for example, they have higher walls made of cut stones rather than rough field stones. This type of high-prestige terraces is also found in other royal Inca haciendas such as Chinchero, Pisaq and Yucay.

The Best Pictures of Ollantaytambo

Videos of Ollantaytambo